Featured image source: Wikipedia

We already got you covered with Five Things Macau Guide Books Won’t Tell You with some really interesting stuff you might not know about this city, which you most probably won’t find in guide books. Now, we take you on a journey through more of these curiosities about Macau!

Did you know how much time it took to cross from Macau to Taipa before the first bridge was built? Or that the Dutch had an important role in local history? These are just two of the things we are covering in this article so be sure to read this through so you’ll have some interesting Macau trivia for your next pub quiz!

Almost colonized by the Dutch

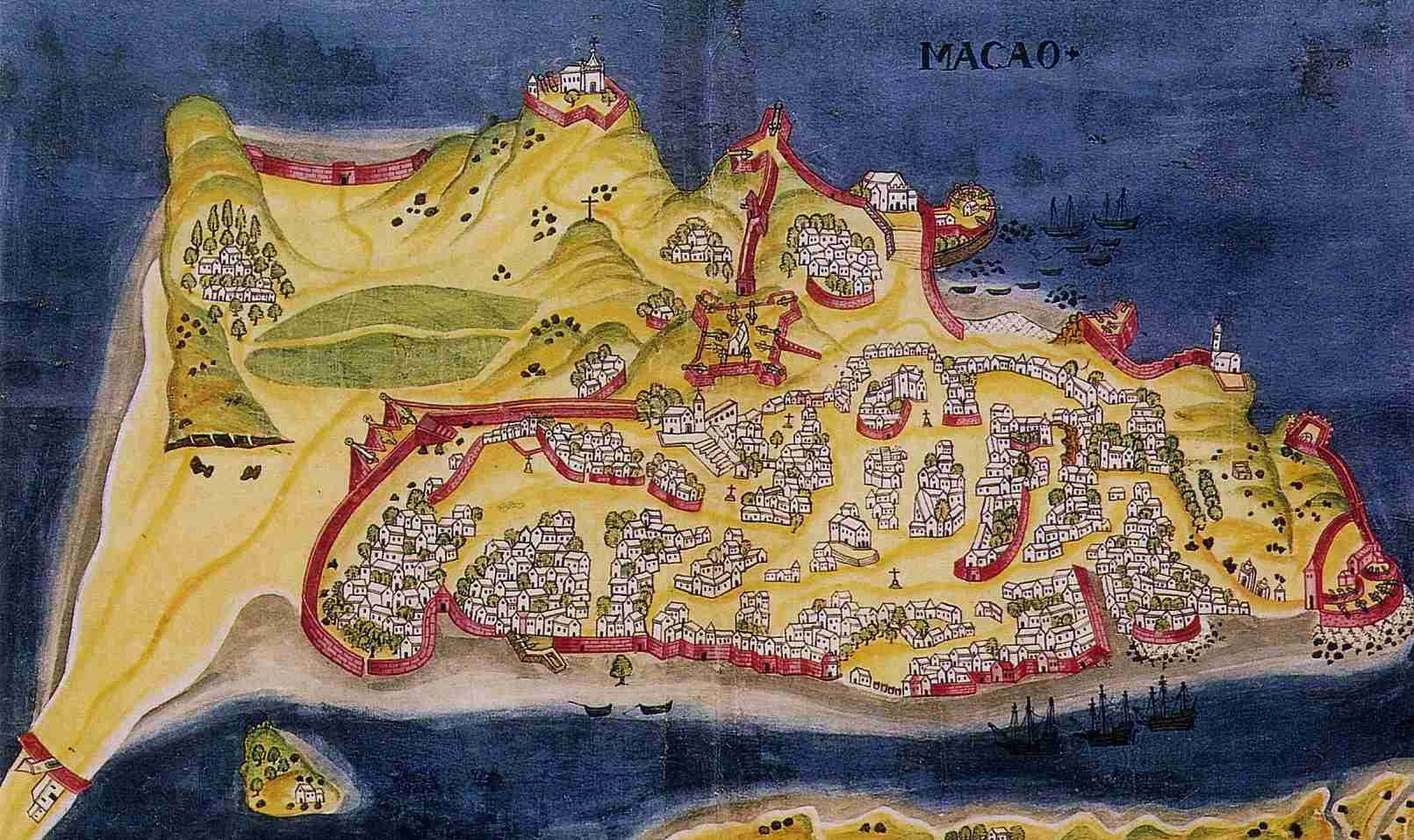

(See featured image above)

This is in fact true! The Netherlands tried–and failed–to conquer the city in 1622. After a political crisis in 1580, Filipe II of Spain took over the Portuguese crown making him the king of both countries. This also made him the ruler of Portugal’s colonies as well, including Macau and others in the Far East. When this happened, these places were seen as part of the Spanish empire, making them as much of a target as the country itself. Spanish enemies included the Netherlands, that wanted to expand their empire as well.

That’s why they attacked Macau. Called the “Macau Battle”, this conflict was part of the Luso-Dutch War and lasted for three consecutive days. Official Portuguese records say between 600 and 800 enemies died, while the official Dutch numbers point to 136. The battle was eventually won by the Portuguese, who managed to blow their gun-ship up with the canon on Mount Fortress which is still there, perhaps to remind us of this event. The Jesuit priest who did it is said to have been a mathematician and some believe it wasn’t just sheer luck that led him to become so successful. Until 1999–the year of the transference of sovereignty–June 24 was a public holiday, called the “Day of Macau”, precisely due to this important occurrence.

Photo credit: Wikipedia. Drawing by Barreto de Resende, circa 17th century

The city was divided into two

Macau was once divided into different areas, which was then put into two big groups–the Christian area and the Chinese area. Although passage through both was somewhat free, the division was still perceptible. This was more noticeable during the 17th and 18th centuries when the city was no more than four square kilometers. In a research paper, José Vicente Serrão distinguishes four parts–the Christian city, the bazaar, the Chinese villages and a burial and farming area. “The Christian city was called so because it was where the Portuguese and Luso-Asian were located”, he adds, saying Chinese locals were even discouraged by the then Portuguese government to settle in said area. It was only from 1793 onwards that this behavior shifted, bringing communities closer with time.

The “Portuguese city” was surrounded by a wall and also natural obstacles. It literally had doors that closed at night and it was located in the south part of the peninsula–including Praia Grande avenue going all the way to S. Francisco Garden and St. Francisco Barracks while Penha and Guia Hills and Mount Fortress were its geographical limits. Interestingly enough, the city acropolis–featuring the most important buildings, be it political or residential–was the area where we still have Senado, the Cathedral, but also other neighborhoods like São Domingos, São Lourenço and Santo Agostinho. One can still witness remains of that time, with constructions (now revamped) such as St. Augustine and St. Lawrence churches. The Saint Lazarus neighborhood was also a Christian area but mostly inhabited by Christian Chinese.

The bazaar–or “Chinese city” as it’s also known–was situated on both the north and west parts of town. Then there were other “villages” where the rest of Chinese locals lived, including the Mong-Há and A-Má area which were used for farming and fishing purposes, respectively. Patane, Longtian and Sankiu were also where they lived, among others. In 1830, according to the Swedish historian Ljungstedt (there’s a street in the city named after him) who lived here, there were more than 4,500 Portuguese and Chinese Christians in Macau, while the number of Chinese residents in the bazaar area summed around 30,000.

Also read: St. Lazarus & Albergue SCM: From Leper District to Cultural Hub

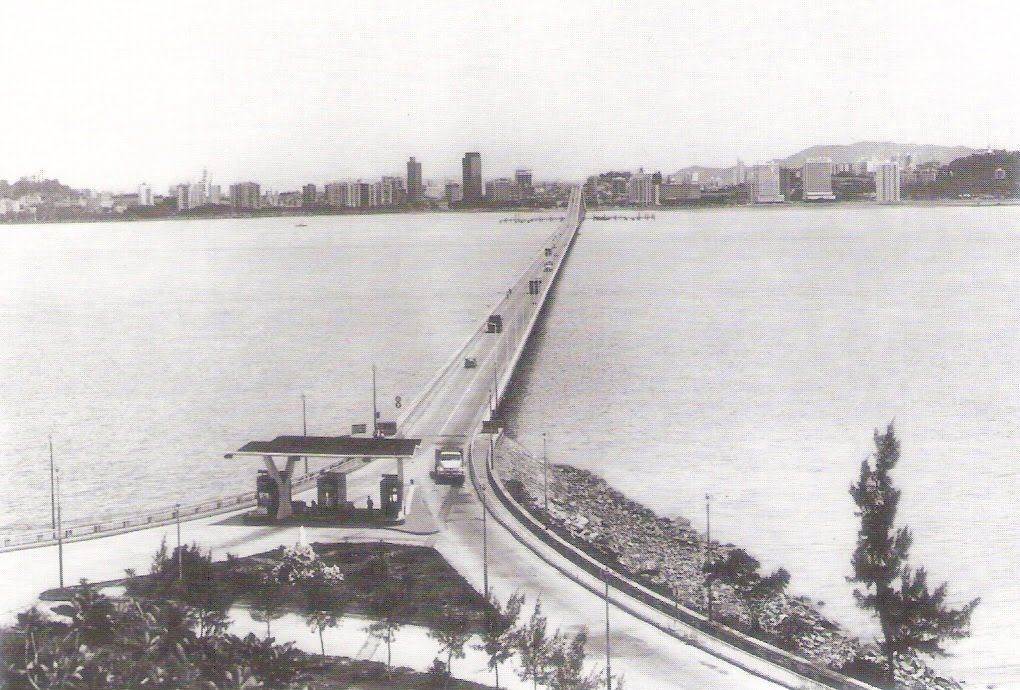

Photo credit: Lee Yuk Tin. Source: Macao Archives

Macau was a small fishermen village

If you did your research when it comes to Macau travel and history, you probably know all about how Macau got its name. In fact, we have an article all about “A-Má” means and how it’s intrinsically related to the city’s history. This goddess of whom there is a statue and temple dedicated to is known as the protector of the fishermen who went to sea.

Well, records actually show that in 1927, fishing was one of Macau’s most important industries, employing more than 20,000 people, including men and women of all ages. However, there were already fishermen–as well as farmers–practicing their trade in the city way before the Portuguese arrived in the territory, prior to 1557. The fishing industry took a serious hit with time and other industries came to surpass it.

Also read: Firecracker Industry: Macau’s First Modern Empire

Photo credit: Wikipedia. Illustration of Ching Shih

Attacked by Pirates–Including A Powerful Woman

Much less a Macau guide book but rather, in history books, did you know that somewhere in the 20th century, some of the aforementioned fishermen turned to piracy, a trade that brought home much more money then catching fish? The Portuguese occupation of Coloane took place in the mid-19th century. When they arrived at both Taipa and Coloane islands, they soon discovered these areas were teeming with Chinese pirates who terrorized the Pearl River Delta and coastline territories such as Canton and Macau. Being so, the Portuguese had to fight them off, having experienced a historical battle conflict in Coloane island in 1910. The Portuguese came out of it victorious.

Curiously enough, one of the most famous pirate gangs was led by a woman. Ching Shih–who was a prostitute before becoming one of the China seas’ greatest marauders–was believed to have been fierce and commanded more than 300 junks and crews of between 20,000 and 30,000, which included men, women and even children. In these cities, she not only took valuables and products but also imposed fees and taxes. Ching Shih attacked Macau too. When the powerful pirate’s husband died, she moved to Macau, opened a gambling house and a brothel, and was involved in the salt trade as well.

Source: O Mar do Poeta blog

It used to take a full hour to cross to Taipa

An interesting nugget of knowledge that isn’t found in most guide books on Macau is how long it used to take to cross to Taipa back in the day. Nobre de Carvalho bridge was only built in 1974, so how would people cross from the peninsula to Taipa side? One could assume people didn’t commute that much at the time. However, they did have to make this journey sometimes. Before the first bridge–now known as the “old bridge” and only available for public buses and taxis–was built, it took an entire hour to get to the other side by boat! This inaugural new project used to have a toll both on Taipa’s end, as the picture shows, according to Official Gazette records, it would cost between MOP $3 and $20 to cross it. The booth was later moved elsewhere becoming a restaurant after tolls were no longer used. Did you know that the public buses we now ride used to have a two-story version? Unfortunately, these were introduced in 1975 but has disappeared since 1992.

Today, one can reach Hong Kong in about an hour by boat or 45 minutes by bus via the HMZ Bridge but it took no less than four hours to follow that same route back then! Older government workers still refer to a kind of special holiday in the calendar as the “Hong Kong days”. They were essential back then and still exist, although not for the same purposes–they enabled people to head to Hong Kong to buy imported goods and products that couldn’t be found in Macau.

This article was originally written by Raquel Dias in June 2016 and updated by Leonor Sá Machado in April 2020.