Featured image: The Triumph of Death (1562), by Peter Bruegel

Epidemics are a serious health matter, but with the leaps and bounds that medicine has made these past few centuries, lifespans have become longer. With the world now facing 2020’s coronavirus threat–COVID 19–both Macau and Hong Kong governments and populations have deployed a set of safety measures and health precautions. SARS is still quite present in people’s memories but there were other epidemics in Macau worth mentioning.

During the start of the 20th century, Macau–including the islands–was no more than 12 km², so it’s not hard to imagine how contagious diseases could harm an entire population. The city experienced its share of epidemics and illness outbreaks. This article sheds light on those, which include the bubonic plague, leprosy and more.

Up until the mid-20th century, Macau was a city were hygiene was not well-practiced. According to the original writings of Portuguese surgeon, Lúcio Augusto da Silva, in a book published in 1864, at the time, Patane and Mong-ha populations were located outside the city’s walls and were comprised of Chinese locals who were known to have bad hygiene habits such as sleeping in the same place as the animals–dogs, pigs, rats, among others. The doctor describes the odor of those streets as “sometimes unbearable”. Locals had little farms on their pieces of land and kept the water from the rain for agriculture, as well as human excrements.

Bubonic Plague–or Black Death (1895)

(See featured image above)

This is still documented as Macau’s most devastating epidemic. The bubonic plague was known to have infected people in Portugal since the 14th century, but Macau was only hit sometime later, in the 19th century. It’s even believed that one of Portugal’s outbreaks has its origins from when a ship (from Macau) with infected mice and fleas docked in Oporto city.

It was 1894 and José Gomes da Silva–the medical chief of the Macau Health Bureau–was summoned by Demétrio Cinatti (Portuguese Consul in Canton) to head to the region and check on a curious new illness that had been killing mainly Chinese locals and rats. It was characterized by high fevers and what seemed to be little insect bites in specific areas of the body. It quickly reached Hong Kong then not long after, it got to Macau as well, in 1895. The same document states that some measures were taken. One of them was at the borders: people coming by boat from Canton and Hong Kong had to go through a medical exam before disembarking. The ones deemed infected were given proper medicine, but when treated with Chinese medicine, western doctors usually found a dead body on the following morning. People were then buried at Portas do Cerco cemetery.

Although Macau wasn’t affected by the epidemic wave of 1894, it was too close to home to not do something. Being so, the Portuguese governor at the time decided that Volong (in St. Lazarus neighborhood), S. Dominic’s Market, S. Paulo (close to the Ruins of St. Paul’s) and Barra areas were areas that needed to be cleansed. In 1885, governor Tomás Rosa ordered the demolishment of Horta da Mitra area. Volong came next and according to Gomes da Silva’s document, it was “fortunate” because it would be “unthinkable” to have the bubonic plague infecting the city with the neighborhood still standing.

Amongst other things, Portuguese governor José Maria de Sousa Horta e Costa (1858–1927) was responsible for the cleansing of entire neighbourhoods, including St. Lazarus, which was a serious source of infections, including the bubonic plague. The same epidemic urged the government to cleanse the rest of the city as well, prohibiting the existence of fecal matter treatment stations inside the walls of the city. As a consequence, areas like Flora, Bela Vista and Adolfo Loureiro stopped emanating a “terrible” smell that until then characterized them so well.

Ka Ho Village Houses formerly used to house lepers

Leprosy (1569–1960)

Leprosy (or Hansen’s disease) is a long-term infectious illness caused by a bacteria and characterized by the damage of human tissue such as skin, lungs, nerves and eyes. Although not classified as an epidemic, leprosy was present in Macau for decades on end. With records going back to 1569, through the 19th century–year of construction of a hospice for lepers in Taipa–and until 1960. St. Lazarus neighbourhood is named so because of a homonymous church. St. Lazarus is the saint of the ill and dying. This area has a house that used to host sick people, where lepers were properly taken care of. In 1569, Portuguese Queen Leonor established the Service of the Holy House of Charity, believed to be the first version of the Holy House of Mercy, the latter established by a Portuguese bishop upon his arrival to the territory. The queen’s institution helped the lepers and was responsible for other charitable works.

This included the inauguration, in 1627, of an asylum for the lepers. According to official records, the perception of hygiene was remarkable for that time, even including “forbidding the sale, in the streets of the city, of vegetables grown in the farms of the lepers as well as animals reared there”. The institution also collected alms to give to the sick on a weekly basis. According to a document entitled Leprosy in Macao (by two local doctors), at the start of the 17th century, the institution housed 70 people.

In 1880, the ill were transplanted to another building, far from the city center, and the St. Lazarus leprosarium was demolished in 1894 amid the fear of diseases spread by the bubonic plague outbreak. The same paper (published in 1938) tells the story of the lazaretto residences built in Ka Ho, which were left incomplete, with just the female wing. The reason? The contractor contracted the disease, leaving the city. After this happened, no one else wanted to take on this job. The doctors’ findings let us know that in 1938, there were around 50 to 60 lepers living in Macau.

Cholera (1858, 1862)

Usually with a deadly ending, cholera hit Macau pretty hard in the 19th century. Once again, the lack of hygiene was at the source of the problem. In 1864, a book was published where Portuguese surgeon Lúcio Augusto da Silva narrates a brief history of this outbreak. “Fai-fum” was how Cantonese locals called this disease. There were two major outbreaks: in 1858 and in 1862.

In just one day (September 21, 1862), 29 Portuguese and Chinese were infected, with more than 100 people contracting this disease. It started by affecting the poor, but it soon spread throughout all social statuses, including the military, people working on boats, among others. According to Augusto da Silva, there were two types of experts to whom patients went to–the Portuguese (western medicine) and the “masters” (Chinese medicine). A chart of his book explains that in September, 22 Chinese locals went to Portuguese doctors, while 277 preferred a master. Cholera killed 106 people out of 421 infected.

Oil painting of Edward Jenner. Photo credit: Wellcome Library, London

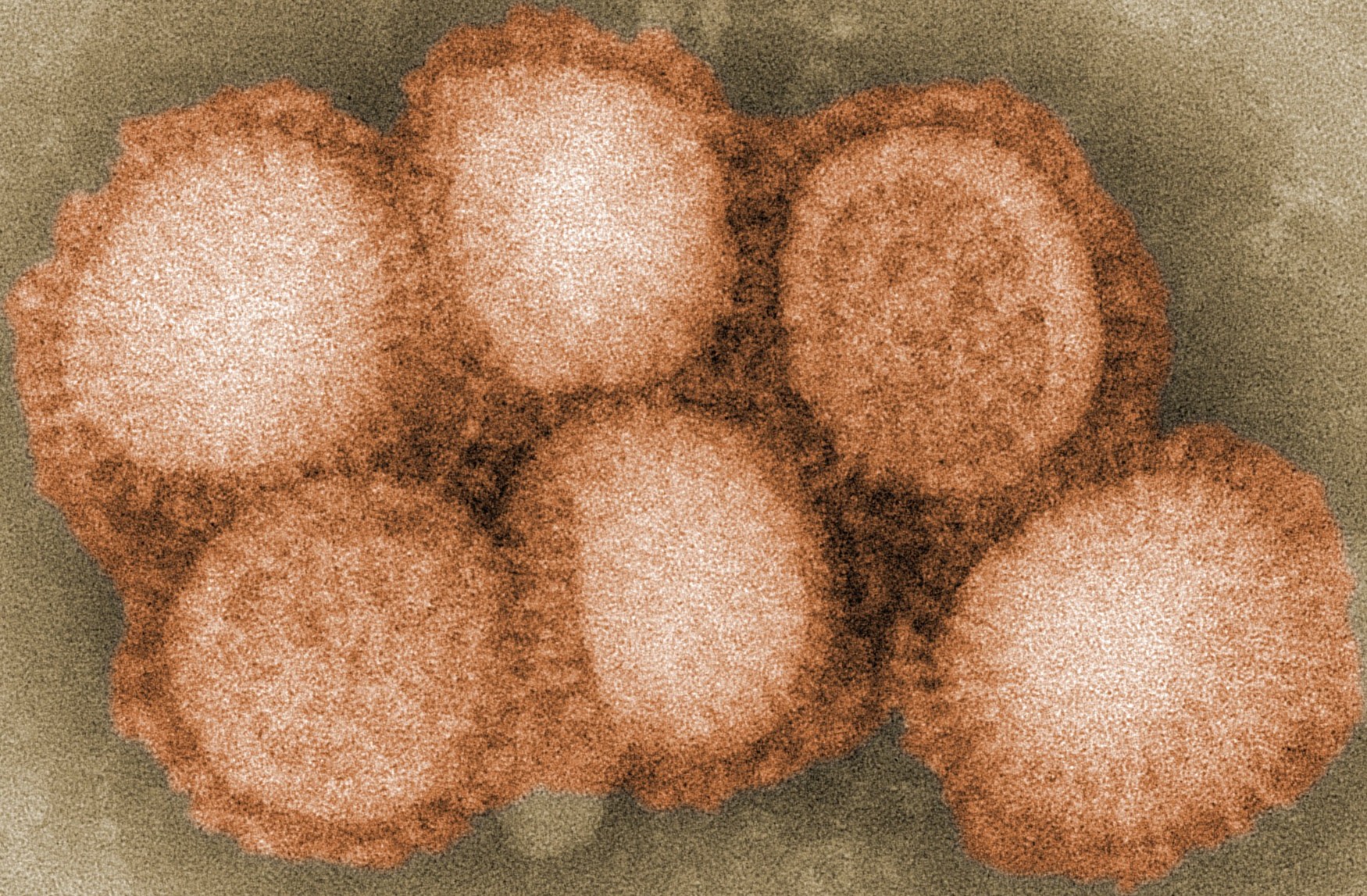

Smallpox (1855–1924)

Yes, people used to die of smallpox in the 18th and 19th centuries. Although a vaccine was already available in the 1800s, less fortunate people had no way of accessing it, therefore extending their suffering. Macau used to have severe and lasting outbreaks of smallpox, which hit the Chinese population the most. Two of the most striking outbreaks of the disease took place in 1855–200 people died–and in 1857, this time taking fewer lives thanks to vaccination. They called it “benign smallpox” since it didn’t register deaths.

Inoculation against this disease had been deployed in China since the 10th century: bits of the dried crust was mixed with water and then inserted in the patient’s nostrils. However, it was only in 1805–when Edward Jenner’s vaccine was brought on a ship from Manila to Macau, by a Portuguese merchant–that the territory got a hold of a more modern version of it. It was first administered to the crew of the ship. In 1806, there were no deaths by smallpox in Macau. Unfortunately, these vaccination campaigns weren’t frequent, leading to several other outbreaks through time. Besides the one in 1855, there was one in 1851 and then in the 20th century, between 1907 and 1924.

SARS–Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (2003–2004)

Known all over the world–and especially Macau, Hong Kong and China–as SARS, this disease killed more than 700 people during its height. Fortunately, there are no reported cases since 2004. In Guangdong, it all started with a fishmonger who checked in at a local hospital, infecting 30 nurses and doctors. One of the latter traveled to Hong Kong for a family gathering; he’s believed to be patient zero in this special region. Official records estimate around 80% of Hong Kong’s cases were contracted from this doctor. More than 8,000 people all over the world were infected with SARS, and 20% of the 1,755 infected in Hong Kong originated at a residential complex known as Amoy Gardens, where it’s believed that a man from Shenzhen visiting a family member was the index patient.

SARS is believed to have passed from bats to civet cats and then to humans. From this epidemic on, surgical masks and disinfectants were the new norms; not wearing a mask when coughing or being ill is seen as disrespectful to others. SARS really did leave undeniable scars all over, especially Hong Kong. It was also from this epidemic that the Macau government decided to build a center for infectious diseases. The use of masks and disinfectant is also widely appreciated in the region. Fortunately, the city registered just a few cases.

Swine Flu–H1N1 (2009)

Classified as a pandemic, the 2009 H1N1 type of flu is believed to have birds as hosts and pigs as intermediates to humans, and was first identified in the United States. It is estimated to have killed half a million people over the course of the first year. In September 2009, the Macau government’s health department identified 1,001 cases of H1N1 within the population.

Between August 31 and September 1, 2009, the same department acknowledged 48 new cases, stating a level 6 on the pandemics scale. News also refers to the existence of a woman infected with the same virus who checked-in at a local hospital, on January, 2011. Fortunately, there is a vaccine for it, in which the elderly and patients with chronic diseases usually get.

Avian Flu–H7N9 (2016)

Typically associated with contagion through poultry, a widespread outbreak of the avian flu made the Macau government take unforeseen measures, such as restrictions on the selling of this kind of meat, and completely banning the trade of livestock at local markets. If you have lived in Macau for more than five years now, you might have witnessed all the hustle and bustle of chickens and other birds at places such as the Red Market or St. Lawrence’s. This is now something of the past.

The first infection in Macau was identified in December, 2016: the 58-year old man owned a poultry stand in the city where he sold live animals. The government killed around 10,000 animals from the supplier market to prevent contagion, including chickens and pigeons. Two previous infections were identified in Macau, but this seller was the first human case. Nowadays, no market in Macau sells live animals.