Heidi Lau’s works reflect the evolution of Macau, the city where she grew up which she visits every year. The city changes every time she visits and that is also very present in her ceramic pieces. Chinese traditions such as mythology and folk superstitions–as well as Macau’s past as a Portuguese colony–also play an important role in her life as an artist.

From Macau she went to New York, having exhibited her work in several international galleries, including the Venice Biennial. We sat down with Heidi Lau to get her take on growing up in the region, but also her life abroad, how it is to be a female artist and more.

You were born in Macau where you also grew up. Can you tell us a bit about being an artist growing up in the region?

I was actually not born in Macau but I grew up and lived there until I was 16. I spent many summers learning Chinese calligraphy and watercolor from my grandpa and was a classically trained pianist but I did not think I would become a visual artist. Looking back though, the Macau I grew up seeing and experiencing was probably the most interesting and magical place and without that beauty and poetics imprinted in my mind, I probably would not have become an artist.

How did New York happen?

I went to New York University and studied Art History and Studio Art. I had considered moving back to Macau after I graduated but at the time neither my family or friends back home were very thrilled about my career choice to be in the arts so I decided to stay in New York where I already have more of an art community.

You work a lot with ceramics. Do you feel this media allows artists to explore a more feminine side of their craft?

It is so interesting to me that you consider ceramics to be feminine because the field of ceramics, both in decorative and fine arts, has for so long been and is still dominated by men. Clay is an extremely expressive medium but I do not think that the medium “allows” artists to be a certain way because the medium is also neutral. It is for the maker to push the medium’s boundaries as well as be informed by the characteristic of it. I also think that self-identified women as such myself can express themselves in any medium they choose: vulnerable, abject, monumental, minimal and not reduced to a term as categorical as “feminine” merely based on the gender they are born with.

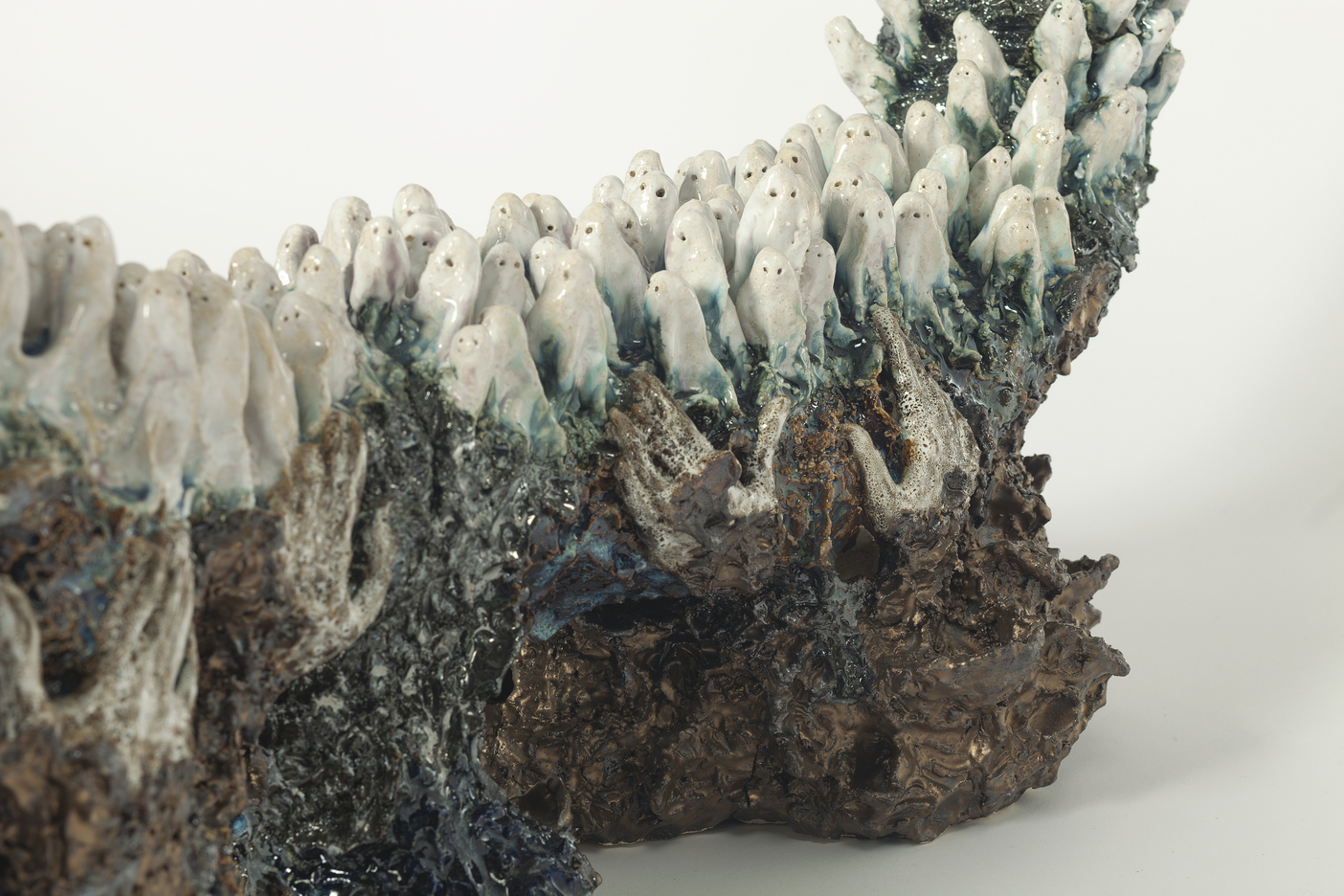

The Seventh and Eighth Level of Hell, Heidi Lau

Taoist mythology, folk superstitions, and Macau’s colonial history are themes strongly present in your art. You live in New York now and keep a deep connection with your roots. Do you find them to be important?

My practice centers on the recreation and reimagination of fragmented personal and collective memories. The history and post-colonial condition of my hometown, Taoist mythology, and cosmology of hell provide source material through which my work explores transcendental displacement and the slippery boundaries between objecthood, monstrosity, and humanity. Painstakingly built, deconstructed and glazed by hand, my ceramic work is the hybridized reincarnation of funereal objects, monuments, and zoomorphic ruins. As one of the oldest and most universal materials associated with productive as well as artistic labor, clay naturally lends itself to the fundamental reconsideration of human activities at large.

You’ve been exhibiting your work in a series of internationally renowned art institutions and events, like the Museum of Arts and Design, the Museum of Chinese in America, the 58th International Art Exhibition of Venice Biennale, among others. How is it to jump from Macau to the world and be able to represent your hometown on a global platform?

I am grateful for all the opportunities that I have worked very hard for and especially to the Macao Art Museum for trusting me to represent my hometown but in general I do not feel or think very much about my platforms or the idea of success at all. As an artist, I feel that the most important task for me at hand is just to be able to live in this world and make work that is truthful.

Your art at the Macau Pavilion (Venice Biennale) focused on the loss of identity and history of your hometown. Can you tell us why you decided to dwell on this matter and how you materialized it?

I think I would like to use the word “linger” instead of “dwell on” because I feel that to say one dwells on certain things, it is already implied those things are negative or that the act of thinking deeply about certain things are negative. I think that history and the passage of time are not so linear and the past is always, irresolvably entangled with our present and future. For my work at the Macau Pavilion and in general, I decided to center on the lived experience or biomythography of many female figures I grew up around in Macau because I believe that the personal is political. Since their stories are embodied in my sculptures, perhaps in some ways we can call it a collaboration with ancestral spirits? And of course, being able to linger on anything is a privilege but also a gesture in this technocratic capitalist world.

Your piece “People Mountain People Ocean” referred to the crowds that fill up the city at all times nowadays. How does this phenomenon affect you? And how do you think it affects Macau’s people?

It definitely makes me feel that so many streets and businesses are not there for the needs of its local people and personally I began developing this kind of double vision where I try to superimpose a mental image of the street I used to know on top of reality to cope with it. I see a lot of different reactions to that phenomenon on social media but I don’t really want to speak for other people.

People Mountain People Ocean, by Heidi Lau

Do you usually let people know your origins? In your own perspective, how do you feel the world sees Macau?

I head home at least once a year to visit my family and I feel the differences in Macau. Most of the time I do tell people my origins, it is a fine balance of wanting representation but also not wanting to be othered. The world sees Macau as how it is portrayed in a lot of mainstream media: ex-colony, Las Vegas of the East, wealthy, Portuguese egg-tarts…

Do you feel that being a woman makes you more sensitive to certain aspects of art?

Being a woman certainly makes me “sensitive” to the fact that as a woman of color in the art world, I have to work at least three times as hard to achieve the same thing as my white male counterpart but I also have data to support this because as a Capricorn woman I appreciate facts as much as feelings.

Is there still a palpable gap between men and women nowadays?

Yes, yes, yes.

How about ongoing and future projects? What’s in store and what can you reveal?

I am currently in a group exhibition “Death Becomes Her” at BRIC (a non-profit art space in Brooklyn) that explores how death and the grieving process impact the living. I will be a visiting artist at the ceramics department of Long Beach University, California.

Every March, the world celebrates International Women’s Day. The 2020 global campaign theme is #EachforEqual. What does it mean to you?

I believe that more than it being a man or a woman’s world, it’s the structure of patriarchy that needs to be re-examined and dismantled, and while this system holds women down, it is actually toxic for most men too. And we can all make small steps by supporting, believing, forgiving and being accountable to other women.

Follow her on Instagram at @heidiwtlau