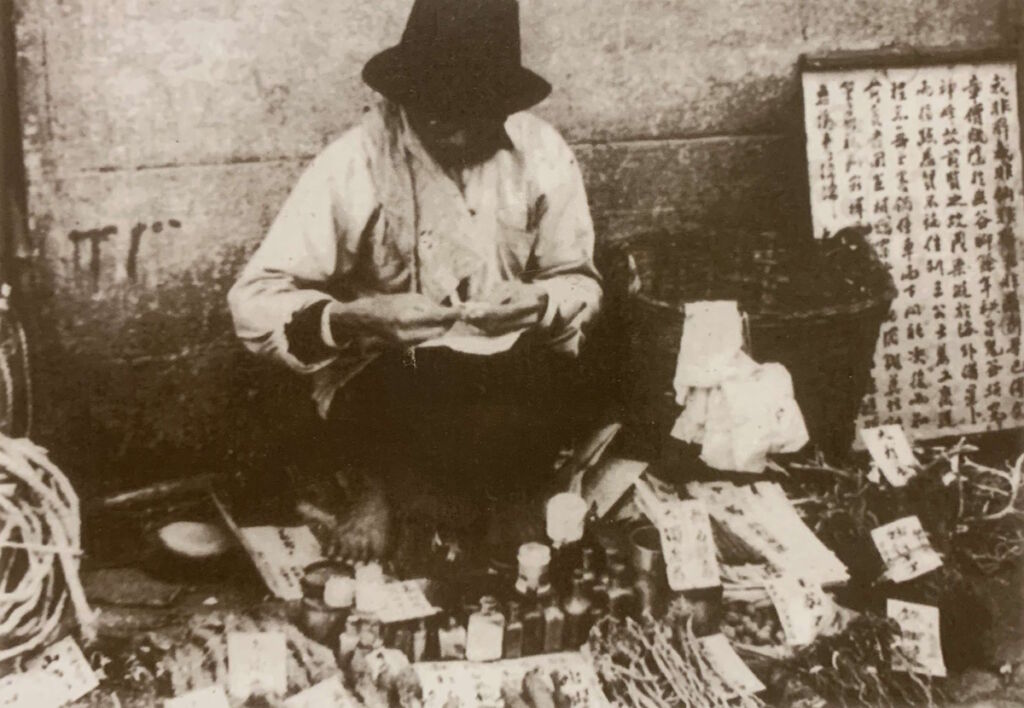

Featured image: Chemist Vendor. Published by the Cultural Institute, 1996. Source: Carlos Alberto dos Santos Nunes

If you dig deep enough into Macau’s history, you’ll find all sorts of curious and interesting stories. Most of these narratives, however, are no longer in the present tense. As any secular society, this small town suffered numerous changes over the years. From being a sleepy fishing village to being ruled by the Portuguese, becoming one of Asia’s main points of commerce exchange and now among one of the richest and most famous places in the world when it comes to gambling, there are loads of stories in between, some really worth telling.

For instance, did you know, not that long ago, Macau was filled with street vendors, where most locals–and some expats–preferred to buy fresh fruits, vegetables, meat, and fish? However, these days, the street vendors are scarcely seen but needless to say, they were definitely part of the fabric of Macau’s history.

Roaming Around: A No-Go for Women

Not just confined to Asia, all the way back in the 18th to 20th century, women from middle and upper society ranks were meant to stay home. It’s either taking care of the kids or organizing soirées with friends and family members who are usually women as well, most of the time. Additionally, men weren’t in charge of buying food, cutlery or porcelain either. So how did people shop without leaving their homes?

According to official records, there were 915 street vendors in 1865, a number that greatly surpassed ones from any other profession in town. Macanese writer, historian and teacher Luís Gonzaga Gomes talks about florists, food vendors, and also silk and patterned materials, clothing, and even itinerant libraries.

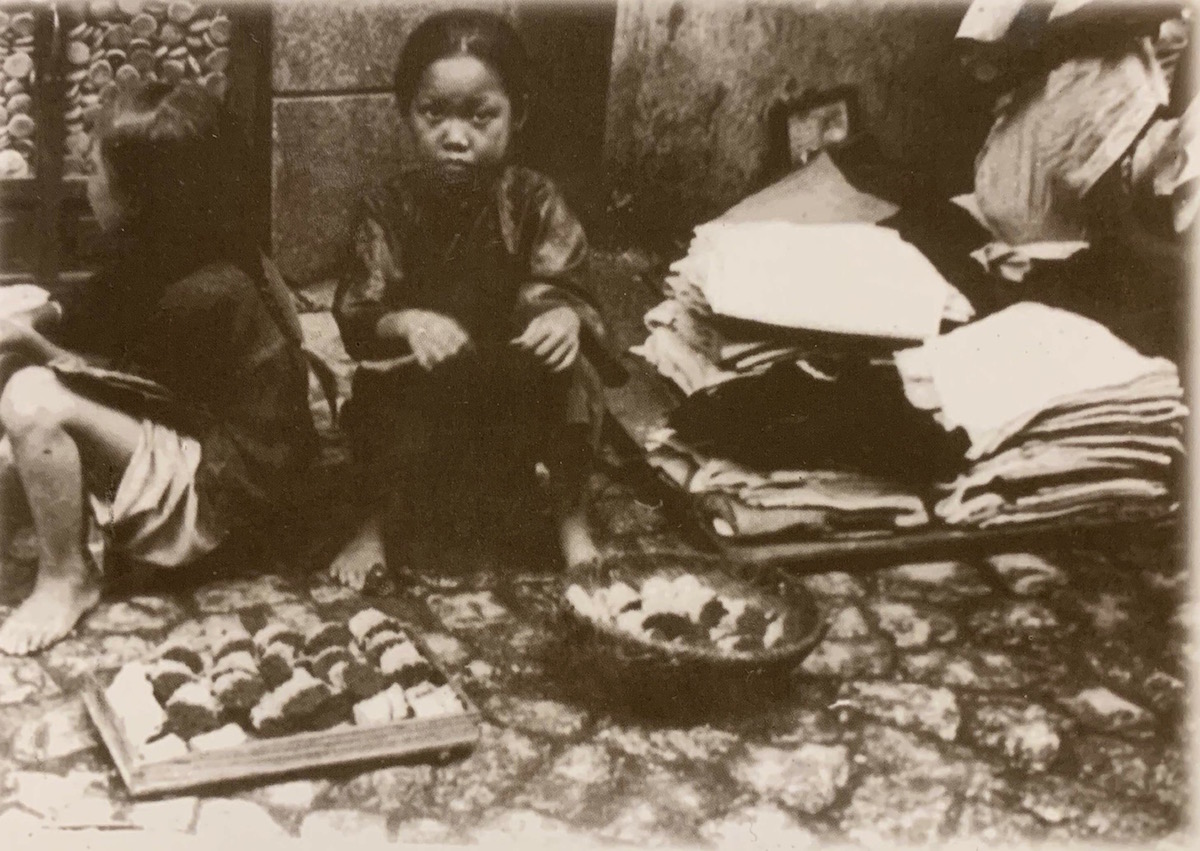

Tableware hawker. Published by the Cultural Institute, 1996. Source: Carlos Alberto dos Santos Nunes

The Importance of Being a Vendor

This is the story of the Macau locals who helped build the society that stands now. Strolling around certain areas–such as Barra, São Lourenço, close to the Red Market or at the Inner Harbour, alongside the river–really brings out the past, reminding us of times gone by. These were some of the areas where vendors of yesteryear sold their goods. One could also find them around Senado Square and its adjoining streets and alleyways. Street hawkers were a common practice in Macau until the mid-20th century, having decreased from then on. Nowadays, one is lucky to find a few of these vendors around.

There were two types of businesses in Macau, the local Chinese and the Portuguese. The latter soon became unsteady due to the evolution of Hong Kong’s economy and openness to the rest of the world but local businesses kept flourishing because people needed them. Hence, the street vendors.

There were many types, which can be separated into two–the stationary and the hawkers, who’d literally go door to door (especially to the homes of people they deemed as regulars) to sell their wares. Everything was sold this way, from porcelain, vegetables and fruits, fresh and dried meat and fish, candy, decor, pots and other cooking utensils and even potable water!

Metals & Scraps

Amongst the street vendors, who usually announced their arrival with catchy sayings out loud, there were the “tim-tins”. Why were they called so, though? Because this was the sound they made upon arrival–a nail knocking on a metallic plaque. This is still a very well known expression amongst the older residents of Macau.

“Tim-tins” sold scraps and all kinds of junk, especially ones made of metal and wood. Records state that they existed way back in the 17th and 18th centuries. Back then, upon arriving in Macau if you didn’t know where to buy things for your first home, the answer was usually “tim-tins”. You could find all sorts of things which were either bought by these poor vendors or made themselves. Scholars are divided on how to classify these hawkers. Are they to be considered itinerant because they had no specific license attached to a spot, or were they more of a fixed business since they didn’t sell door to door?

These hawkers sometimes roamed around looking for clientele, but also stood at regular places where they predicted that more people would walk past. An official source from 1861 makes reference to heaped scraps at S. Domingos area, for instance. Historian and writer Ana Maria Amaro has also published on the matter. “Used to their clientele’s routines, they started establishing a schedule of sorts, in S. Domingos area, around 5:00pm or 6:00pm, the time people left their offices”.

Chinese New Year was a golden time for these vendors, since most locals like renovating their homes for the year to come. The “tim-tins” benefited in two ways–they’d get stuff from the richer Chinese who got rid of old belongings, then selling them to the less fortunate with the same desire of starting the year with something “new”.

If you talk to someone who’s lived in Macau up until the 80s, you might still hear something that’s close to the “tim-tins”. This means what you’re looking for is located somewhere around Senado, namely Rua dos Ervanários, Rua da Nossa Senhora do Amparo and Rua das Estalagens. In Portuguese, they’re also known as “little tents” (tendinhas).

As time went by and trade slowly moved from the streets to proper shops, these pieces too started being sold in-store. There are still some of these along Rua dos Mercadores and Rua das Estalagens as well. Besides tableware–some old and rare–one can also find beautiful antiques with Chinese and Macau motifs that’re really worth seeing.

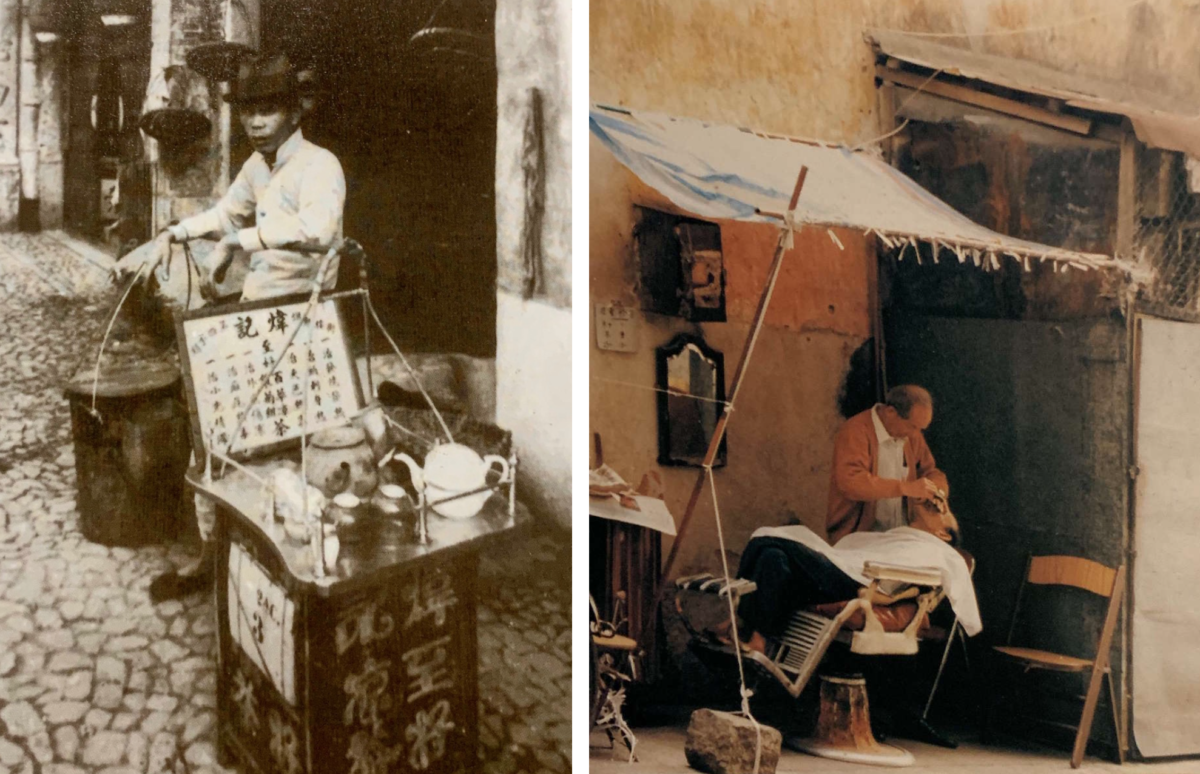

Matches and Clothes Vendor. Published by the Cultural Institute, 1996. Source: Carlos Alberto dos Santos Nunes

From Door to Door

Some people still recall having vendors at their homes selling everything, some on a regular basis, like a shoeshiner, hairdresser or barber. In fact, bread was also sold door to door, daily. We heard stories about Macanese families who would have men selling them beautiful Chinese-style embroidered towels by ringing the bell, while other gentlemen preferred having their shoeshiner go to their home so they could go out with shiny moccasins.

There are all sorts of stories out there and no names are worth mentioning because this was not a practice of a particular family, but of most Macanese and Chinese middle and upper-class families. Water was yet another essential–municipal water was never deemed by the population as potable, even when it was classified as so by the local government. Back in the 20th century, bottled water was expensive, so people would buy water from a lady who also went door to door. She’d knock on each door, presenting herself with two big plastic containers tied to a long and strong bamboo stick that she carried on her upper back. People would store the water in huge buckets which were later boiled to make sure it was safe to drink.

There’s also a story–told by anyone who’s more than 60 years old and has lived their childhood in Macau–about a man with a small chee cheong fan (rice noodles, a Cantonese specialty) stall who cut this delicacy into pieces with the same scissors he used for his nails. Some say this was the best chee cheong fan in town and why not, with the additional “flavor”?

Tea Hawker (published by the Cultural Institute, 1996. Source Carlos Alberto dos Santos Nunes) and barber (source: book Vendilhões de Macau)

Sitting, Waiting, Wishing

There were also vendors with a small stall or simply a steady place where they could go about their business. There were food vendors selling meat, fish, fresh vegetables and fruit, barbers, hairdressers, and many others.

Rua da Felicidade was also a crowded place when it comes to shopping, especially flowers–perfect place to buy some “happiness”, we might add. We can still spot some vendors around the city, especially those selling food. Areas like Rua dos Mercadores, alleys around the Red Market neighborhood and corners of the inner harbor leading to Barra are still filled with locals carrying carts of hot, freshly made food. There is also a cookie master selling them close to the Holy House of Mercy, right in Senado. If you’re looking for a traditional and comforting dessert with decades of flavor and experience, check out Tat Kei Dessert where two women with a cart serve up sweet warm dessert soups.

Also read: Tat Kei Dessert: Four Decades of Sweet Soup in Macau

Dough Puppets Maker. Published by GCS

Sweet Heritage of Mine

It was 2008 and the Macao Museum was celebrating 10 years of existence. It was also drafting a project to have a very specific part of Macau made part of the region’s intangible heritage–rice dolls just like the ones in the photo above. The museum’s former director, Chan Ieng Hin said that there were a lot of shops and artisans making these in the 90s, but not so much (around two or three shops) at the time of the said project.

These were very popular during the 50s and 60s, especially among the little ones because of its bright colors and fun looks. It’s said that the creators of these dolls were true artists, crafting faces and tiny details onto homemade flour or glutinous rice paste. The efforts to make this a national Chinese intangible heritage–alongside things like Macanese gastronomy–was reached, and it’s still kept in the memory of older generations.