Located in hidden and narrow Rua da Palmeira, the now museum Patane Night Watch House is a reminder of Macau’s past. It takes us back to the 19th and 20th centuries when the night guard was a key character in helping to promote safety and security in the streets and the community. Sadly, all the night watch posts in the city were gradually demolished, all but one. It can be visited for free and it’s well equipped with old accessories and original artifacts from back then. If you’re a fan of history and want to know more about this ancient craft, read on before heading there for a tour.

Chinese legacy

Night watchmen were abundant in Chinese cities and villages. Their main task was to let citizens know what time it was–which they did by sounding a gong–as well as warn them about fires and assaults. It was a pretty useful profession, but also a great example of the way things worked, especially in smaller areas like villages. It’s also a symbol of how citizens counted on each other and their own community as a whole to make the system and their daily lives work. Servicing the community was something relevant.

Its decline in popularity and importance over the years is also a sign of the changes in values and ways of living of the Chinese. Globalization is a term of present times, but it’s been going on for decades, if not centuries.

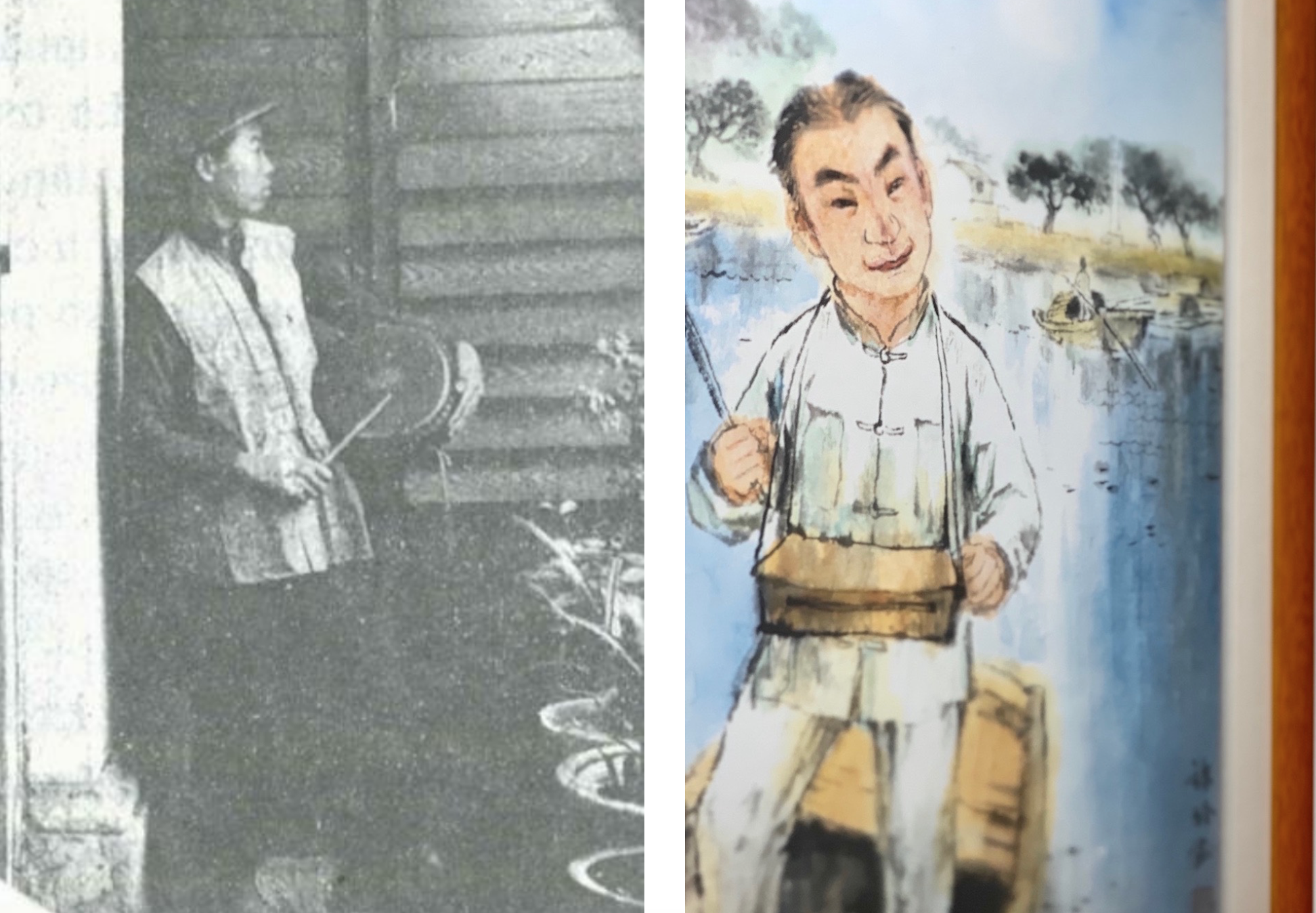

Photo credit: (Left to right) Leonor Sá Machado and Coisas de Macau (1913), by Álvaro de Melo Machado

Beating the gong since the 19th century

Macau was no different; there were also night watchmen at a given time, although they were later replaced by professionals with military backgrounds, a defensive force with a stronger, more official structure. Official information tells us there were almost 100 watchmen working in Macau in 1867. Some info suggests there were night watch houses in Macau during the “9th reign of the Qing Dynasty’s Guangxu emperor”.

There were night watch houses scattered across the city, namely in the Sam Kai area–which includes Rua dos Mercadores, Rua das Estalagens and Rua dos Mercadores, Mong-Há hill, San Kio, and the then island of Taipa.

According to the information available at the Patane Night Watch House, one night was divided into five different shifts, starting at 7:00pm and ending at 5:00am. Each shift change was announced by the sound of the gong, which was different at each hour. There was a gong beat at the first shift, two beats at the second, and so on, according to reports from older people from Taipa, where there used to be night watch houses as well. However, one might wonder how they counted time since clocks were not yet popular back then. In Macau, they’d use conventional methods such as burning incense–and using the time it took to burn it as standard–or by using a clepsydra, a clock made with water.

Before fire departments were a thing, it was also the watchmen’s task of helping to put fires out or any other disaster related to the community such as typhoon signaling, among others. Each night watch used to be equipped with lanterns, alarms, a map of the city, a chart with fire and typhoon signals, a firemen’s car, water pistols, and other tools.

The costs of maintaining the night watch house were usually supported by local residents living in the respective area and merchants with shops there as well, as a means of protecting their own lives and businesses.

In 1936, the then Portuguese government updated the legislation and included these professionals, stating they’d be working under the supervision of the police department. The legislation stated that watchmen could only be active until a certain age and, as time went by, some aged out of the profession and no one else replaced them, thus causing a decline in this craft that started in the 1970s.

Patane’s Night Watch House: Much More than Public Service

Rua da Palmeira–where the museum is located–used to be Patane’s main artery. According to a book by Wenda Wang on stories of Macau, Patane was one of Macau’s busiest and most populated areas, mainly by the Chinese. So much that several high-ranking officers living in Macau, of both Ming and Qing dynasties (the last two Chinese dynasties), moved to the neighborhood.

As the only watch house still standing, Patane’s one has been renovated by the local government to become a free admissions museum that people can visit and find out about this profession and its past. The first photograph proving the existence of the building dates back to 1940–decade in which it’s believed to have been built–although it’s believed these existed before. Besides being used as a watch house, the building was also the former watchman and his family’s household up until the mid-1960s.

Unique Construction

Patane’s night watch house is located in a land with approximately 80 square meters and was comprised of the main building with a single floor, a patio, a stone compartment, and a water canal, an example of the architecture of old traditional Cantonese homes. This construction is considered unique because of its connection with the adjacent buildings, which wasn’t the case with other night watch houses; it’s also very characteristic of other examples of architecture from decades ago specifically in Patane.

The stone chamber inside confers this venue a special and unique design. It’s connected to the popular Tou Tei Temple. However, this watch house wasn’t always located there; it was first functioning inside of a government office, and then it was relocated to its present location.

When the need for these houses started declining, in the 1970s–with some of the other watch houses around Macau being demolished–the building was then used for other purposes, even a café and later as a sports club at a given time. It was in 2010 that the government decided to revamp it and turn it into a museum people can visit. However, it was only in 2015 that the place was officially opened to the public as a museum, thus spreading the word on this old craft, an important and relevant part of the city’s and region’s history.

Opening hours: Tuesday–Sunday, 10:00am–6:00pm

Old Patane Night Watch House 52–54 Rua da Palmeira, Macau, +853 2836 6866